|

"SPECIAL EFFECTS: WIRE, TAPE AND RUBBER BAND STYLE by L.B. Abbott"

Pieces from The Towering Inferno-chapter

(Special thanks to Jim Vines, who provided me this great stuff!

to Dana Stringos who captured the last 3 big pics from DVD,

and to Michael Jehn who made some bigger/better scans of the Tower-model pics.)

My biggest task on this picture was the photography of the miniatures. A 138-story building in half-inch scale is 70 feet high. To have built it in a larger scale would have made it impractical to  place a camera above it to make down shots, which were a must. The half-inch scale of the Tower made it mandatory that the fires be in half-inch scale. Small-scale miniature fires are notoriously unsatisfactory; they are lazy and transparent. With this in mind, I decided to see if we could cure the disease. place a camera above it to make down shots, which were a must. The half-inch scale of the Tower made it mandatory that the fires be in half-inch scale. Small-scale miniature fires are notoriously unsatisfactory; they are lazy and transparent. With this in mind, I decided to see if we could cure the disease.

We built a metal mock-up of 10 windows, each six inches square. We had decided that the use of

any inflammable liquid would be far too dangerous and that we would have to use gases. Behind each window, therefore, we built a metal firebox eight inches deep with openings six inches square. The back was a wall curved forward at the top of the window so that when the windows were on fire the  flames would tend to escape at the top. Each box contained three jets, one emitting butane gas, one emitting acetylene gas, and one emitting air. Each gas jet was equipped with a spark plug ignitor. Butane gas makes a slightly blue-colored flame and no smoke; acetylene makes an orange-colored flame and produces some black smoke. With this combination we could ajust the valves to get the proper color and amount of smoke. The air jet was used to agitate the flame action. flames would tend to escape at the top. Each box contained three jets, one emitting butane gas, one emitting acetylene gas, and one emitting air. Each gas jet was equipped with a spark plug ignitor. Butane gas makes a slightly blue-colored flame and no smoke; acetylene makes an orange-colored flame and produces some black smoke. With this combination we could ajust the valves to get the proper color and amount of smoke. The air jet was used to agitate the flame action.

After three days of testing we came up with a formula that produced very acceptable half-inch scale fires, when photographed at three times normal speed (72 fps). Overcranking was necessary because we knew that some of the scenes would have falling dummies and water action.

The next struggle was to find the proper gold color for the building. As you may know, the color is dependent largely upon the reflectiveness of the paint. We went through quite an extensive test series for both exteriors and interiors before we found a color that pleased the producer, Irwin Allen. The ½-inch scale Tower and the Peerless building were set up on the concrete floor of Sersen Lake. The Tower was so tall and narrow that we guyed it off in four directions with steel cables whenever we were not photographing it.

In order to get a low horizon for Fred Astaire's first POV of the Tower, we used a mirror. We also built the top 40 stories of the tower in 1½-inch scale at a location some distance from the ½-inch scale miniatures for compatibility with the 1½-inch scale miniature helicopters that were available.

(.....)

The opening shot, showing Paul Newman's helicopter flying across the city and making a climbing circle to land on the heli-pad on the top of the Tower, was made from a roof top in San Francisco. When the chopper crossed in front of the miniature buildings, which had been inserted into the San Francisco cityscape using the matte shot technique,  we rotoscoped it. In other words, a hand-drawn matte was made of the chopper on each frame in which it was backed up by the miniature buildings. we rotoscoped it. In other words, a hand-drawn matte was made of the chopper on each frame in which it was backed up by the miniature buildings.

Prior to the start of production, I spent the better part of a month in San Francisco and at sites across the Bay so that we could get some long and medium shots of the buildings at night while the Tower is burning. These shots were made at the magic hour. The lights in the city were on and there was enough reflected light from the sky to make a very believable night shot with some detail in the buildings.

This material was photographed before the miniatures were shot and four of the scenes were used at various times during the picture. When the action in the miniature fit what we needed in one of these night shots, we placed the camera in the proper spot and, using a line-up clip in the viewing tube, framed it so that the miniature would be in the right place when it was matted into the scene.

One such shot, for example, comes early in the picture during the opening-of-the-building ceremonies. In this scene, as part of the act, the interior lights of the Tower were turned on in ten-floor increments from bottom to top. The electrical department rigged the circuitry to make this possible and the scene was impressive. (.....)

Shortly after the lighting ceremony, William Holden ushers the principals into the lobby and aboard a large elevator that exits the building and travels on the outside of the Tower to the 139th floor, where there is a huge roof gardenrestaurant. This set was highly unusual. The floor space, on many levels, covered 11,000 square feet. The lowest level was six feet off the stage floor and the ceiling was 12 feet above that. Three sides of the set were backed by a 340-foot cyclorama. This was an excellent piece of artwork done by Gary Coakley and his crew.  The view depicted in the backing was what one would see looking from a vantage point 1500 feet above the center of San Francisco across the bay to the Oakland side. The lights in the distant cities were on, and some of them were blinking. There were even reflections of the lights on the water. The lights were made by punching small holes in the backing and placing small quartz lights three feet behind them. The blinking lights, representing aircraft warning lights on radio antennae and high hills, were lighted with red Christmas tree blinkers. The shimmer on the water was simulated by cutting slightly curly slits in the backing and hanging silk strips behind the backing. The strips were lit from three feet behind and activated gently by fans. (.....) The view depicted in the backing was what one would see looking from a vantage point 1500 feet above the center of San Francisco across the bay to the Oakland side. The lights in the distant cities were on, and some of them were blinking. There were even reflections of the lights on the water. The lights were made by punching small holes in the backing and placing small quartz lights three feet behind them. The blinking lights, representing aircraft warning lights on radio antennae and high hills, were lighted with red Christmas tree blinkers. The shimmer on the water was simulated by cutting slightly curly slits in the backing and hanging silk strips behind the backing. The strips were lit from three feet behind and activated gently by fans. (.....)

In a (...) sequence, McQueen has arranged that a Coast Guard helicopter set up a breeches buoy cable between the garden and the Peerless Building roof.  We built a section of the Peerless roof and backed it up with a blue screen. This way, we could show the women who were first saved arriving on the Peerless roof. The figures enter from above the frame and in the background is the burning Tower, shown in plates we had made of the burning miniature. (.....) We built a section of the Peerless roof and backed it up with a blue screen. This way, we could show the women who were first saved arriving on the Peerless roof. The figures enter from above the frame and in the background is the burning Tower, shown in plates we had made of the burning miniature. (.....)

The next is a miniature up shot holding a portion of the miniature Peerless Building and the 1½-inch scale Tower. The chopper lifts a dummy of McQueen off the roof and heads toward the [scenic] elevator. He lands on top of the elevator in the full-size set. (.....)

To back up the close cuts of McQueen and the cage with the passengers during the descent, we moved an 80-foot section of the bay view backing to an empty stage where we could use a large crane to drop the cage.

Having this backing on a stage where I could get at it was a real plus for me. I had been puzzling for months as to what I could use to back up the first ascent of the outside elevator in the opening of the picture. We had shot the people in the car against a blue screen and that was still all we had. While in San Francisco I had shot a plate from the outside elevator at the Mark Hopkins, but the run was too short for the scene. I had also tried making the plate from a chopper starting as low in the city as the law would allow and rising straight up. This didn't work out because the chopper always swayed from side to side.

I had really been procrastinating, halfway thinking that I could solve the problem either by doing some expensive artwork or by relocating the chopper plates by hand, frame by frame-a tedious and expensive proposition. As I looked at the backing while we were shooting the elevator, I got an idea.

We set up some miniature buildings (which we had in stock) on the floor some 25 feet in front of the backing and mounted the camera on a crane. As the crane raised, I tilted the camera down to hold the horizon in the same place during the climb. I was very relieved when all concerned were pleased with the plate.

We used the 1½-inch scale burning tower miniature for all the scenes involving the helicopter because the chopper was in that scale. After completing the helicopter scenes we needed some footage showing the fire consuming the Tower. We spent a considerable amount of time adjusting the valves controlling the gas and air pressure on each floor. Unfortunately, when we turned the whole system on, the ignitors didn't work immediately. After about 10 seconds they did work and there was one hell of a big explosion. This cut has been used more times on TV spots than any scene I have ever been involved in.

When the explosion occurred, a lot of debris fell from the building. I was standing adjacent to one of the cameras and was so awed at the explosion that I didn't see my personal menace coming. A four-inch by four-foot piece of L-shaped metal imbedded itself in an upright attitude about six inches from my right foot. Fortunately, no one was hurt. From then on we made it a point to have a roof over our heads. (.....)

Newman remembers suddenly that there are five huge water storage tanks on the roof. McQueen indicates there is a good chance that the water would extinguish the fire and that they must try to blow up the tanks and release the water as soon as possible. McQueen gets the explosives and goes up to the roof by chopper, while Newman climbs an interior shaft to the top.

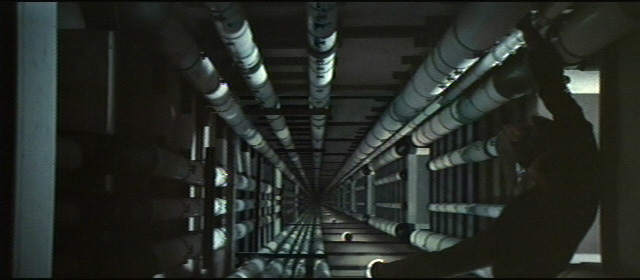

We built a vertical 6' x 6' x 20' shaft. The bottom was raised five feet above the floor to allow us to put a blue screen on the floor and light it. We then placed the camera directly above the set. Shooting straight down, we photographed Newman climbing toward the camera from halfway down the shaft. Then we made some footage of the empty shaft from the same angle.  When the composite was made, we reduced the empty set so that the top fit the bottom of the set with Newman in it. By adding a little art work we managed to make the shaft appear to extend down hundreds of feet. When the composite was made, we reduced the empty set so that the top fit the bottom of the set with Newman in it. By adding a little art work we managed to make the shaft appear to extend down hundreds of feet.

We used the central heating and air conditioning plant for all of Century City (the palatial business district adjacent to Twentieth Century-Fox) for the basic storage tank set. This complex has only two tanks in it, so we built a miniature of the tanks and some of their surroundings. By adding some matte paintings we produced a composite for the complete set. (.....)

McQueen and Newman work feverishly planting two charges on each of the tanks. (.....)

When they return to the garden, we cut to the miniature and the tanks as they explode. In order to show the water crashing through the roof garden set, A.D. Flowers designed a new type of dump tank. These tanks are metal cylinders six feet long and five feet in diameter with a three-inch diameter pipe running through the center. In the skin there is a three-foot wide opening the length of the cylinder. The center pipe extends 18 inches beyond each end of the tank when mounted on a supporting structure. These pipes extend through bearings in the structure and a three-foot steel wheel is attached to one end.

To operate the tank, the opening in the skin is placed at the top and the tank is then filled. A man holding the wheel is then able to revolve the cylinder at any desired speed. The faster it is revolved, obviously, the quicker the water is released. Inasmuch as the man revolving the cylinder is not actually moving any water but only the tank itself, very little effort is required. These tanks hold 800 gallons each.

A.D. positioned four of these tanks above the garden set and backed himself up with several high pressure fire hoses that would extend the length of time the water could be kept flowing.

The sequence of the garden being flooded as filmed by the action unit is probably the most exciting highlight of the film.  The miniature intercuts to the exterior of the tower were done by placing a small dump tank and a high-pressure hose on top of the 1½-inch scale set. As the water cascaded down, we doused the fires. We also covered this action on the ½-inch scale miniature set. The miniature intercuts to the exterior of the tower were done by placing a small dump tank and a high-pressure hose on top of the 1½-inch scale set. As the water cascaded down, we doused the fires. We also covered this action on the ½-inch scale miniature set.

This marked the end of a very challenging task for me. It was an unusually well-accepted picture.

Much of the credit for the succes of the visual effects of The Towering Inferno belongs to some of my special helpers. In particular I should mention the late Frank Van der Veer and his optical company, for assembling the blue screen composites and matte shots; A.D. Flowers and Fred Kramer, for making the fires burn; and the late Bruce Hill of Hill Production Services, for providing the remote controlled pan and tilt head and videomonitored camera; and Paul Wurtzel, head of the mechanical effects department at Twentieth Century-Fox, who gave complete help and cooperation on Towering Inferno-and many, many others.

[Most of the skipped pieces - marked (.....) - contain fragments of the story and we all know that, don't we ?!]

|